Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, 1833. Edmund Kean, the greatest actor of his generation, has collapsed onstage while playing Othello. Ira Aldridge, a young, Black American actor has been asked to take over the role, but a Black man has never played Othello on the English stage before. His groundbreaking performance upends centuries of British stage tradition and changes the lives of everyone involved.

As anti-abolition riots take over the streets of London, how will the cast, critics, and audience react to the race revolution taking place in the theatre?

Director Cherissa Richards (The Power of Harriet T, Manitoba Theatre for Young People), recipient of the 2021 Crow’s Theatre RBC Rising Star Emerging Director Prize, returns to Crow’s after working as Assistant Director on MixTape last season.

for more info and video footage see -

https://www.nowplayingtoronto.com/event/red-velvet/

________________________________

Lolita Chakrabarti’s 2012 play, Red Velvet, is a powerful two act tour de force for a cast of eight characters as they inhabit the world of 19th century theatre where very particular styles of acting, and casting, dominated the consciousness of many theatregoers. This dominance, of course, was entangled with vehement racism and played an historical part in the long and arduous history of black actors being denied the possibility of playing black characters, Shakespeare’s Othello in particular.

As director Cherissa Richards says in the program notes – “We often think Paul Robeson in the mid-twentieth century was the first Black man to play Othello in London” – and goes on to say that it was, in fact, Ira Aldridge (1807-1867), an African-American thespian who, at age 15, joined the Manhattan based ‘African Company’ and left New York in 1924 after finding it difficult to secure theatre work in the U.S. Aldridge was able to get roles at London’s Royal Cobourg Theatre (now The Old Vic), performing under the name of ‘Mr. Keane, Tragedian of colour’ -as a tribute to the acclaimed Shakespearean actor of the time, Edmund Keane.

Ira Aldridge

Becoming the first Black man to play Othello, over one hundred years before Robeson, Aldridge entered the theatre during a time of great change in acting styles, and an ongoing systemically racist time that begrudgingly allowed actors of colour to take roles clearly written for people of colour.

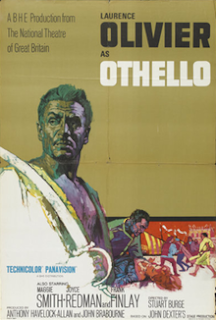

This tendency, particularly in the case of Othello, continued well into the 20th century, with perhaps the most famous examples being Orson Welles’ contemporary adaptation in the 1952 film ‘The Other Woman’ and Laurence Olivier’s 1985 cinematic mess where he played the role in blackface, adopted an invented accent and a very particular way of walking. One could call it method acting, but by doing so, without revealing the racist tendencies frequently apparent in mimicry, a lot would be missing from the extremely problematic racialized equation.

Laurence Olivier in Othello, 1985

But apart from all the deplorable historical detail, there lies Chakrabarti’s play, promoted by Crow’s Theatre as “an imagined version of true events.” The playwright has utilized, to powerful effect, Aldridge’s career, and the time period, within a traditional theatrical structure, in order to create a fable like kind of realism that heightens the intent and brings it to twenty-first century audiences in an effective, fast-paced journey through a moment in Aldridge’s career.

The ensemble, led by Allan Louis in the lead role, is directed by Cherissa Richards with great intricacy as actors must move seamlessly in and out of nineteenth and twentieth century acting styles – styles that began to mingle and evolve during Aldridge’s career. This is no easy task, and is handled expertly by all of the actors. Jeff Lillico as Charles Kean and Ellen Denny as Ellen Tree enact flawless transitions between styles. Lillico, in particular, has intense and convincing moments of passion when his character reveals the racialized biases contained within the differing styles. Thomas Ryder Payne’s sound design punctuates, especially in the final dream-like moments, the non-stop struggle and conflict at the heart of the play.

Louis, as Othello, creates a highly charged and diverse intensity as he inhabits the role of Aldridge, punctuating every scene with passion and emotional fervour that reveals layers of sensitivity and bewildering challenge in the face of his detractors, both on and offstage.

Coming in at around two hours, with one intermission, the Crow’s production is a compelling and timely reminder of an ongoing tragedy that still occurs on streets, live stages, and in the cinema worldwide. The imbalance around representation, and the actors chosen to play various roles, continues to play a dominant part, despite notable exceptions, in the systemic racism of the 21st century, nearing two hundred years after Ira Aldridge became the first black man to play Othello.

________________________________________

"Why is Ira's legacy forgotten? Why did this man who changed the world of British theatre disappear into the ephemeral mist of our memory? Why aren't theatres named after this iconic trailblazer? Why is he a mere footnote in the faded memories of our great Shakespearean actors?...

Almost 200 years after Ira made his London debut as Othello we find ourselves asking the same questions, and more. When change comes banging at our door, will we be ready for it? When the flames of change come roaring through your door, whose hand will you reach out for?"

Cherissa Richards, DIRECTOR OF RED VELVET

_________________________________

red velvet runs at crows theatre until December 18th

https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/16686673-red-velvet